I started to use IPython, and then Jupyter more than ten years ago but despite of all the nice features, there were always something missing, something that prevented me from using it as my main working environment. Notably, Jupyter lacks

Line by line execution of scripts: The basic execution units of Jupyter are cells so there is no easy way to execute, tweak, and re-execute pieces of the code for debugging purposes (StackOverflow Question, Jupyter Issue 1094). The problem here is not how to execute parts of the cell content, but where to execute the code and display the output. You could use a scratchpad extension to execute scratch cells but this is still less convenient than the line-by-line execution mode that you are used to in other IDEs.

Support for multiple kernels in one notebook: Jupyter supports virtually all scripting languages ever invented but each notebook can only use one of the kernels. With increasing complexity of modern data analysis, especially in the field of bioinformatics, analyzing data with more than one scripting languages has become more and more a necessity. Keeping the entire data analysis in a single notebook has obvious advantages in the book-keeping and sharing of data analysis, and allows better reproducibility of prior analyses. Unfortunately, despite of the emergence of several multi-language notebooks such as R Notebooks, Apache Zeppelin, and Beaker Notebook (Now BeakerX), Jupyter (even JupyterLab) does not seem to be moving in this direction.

Literate programming and some other usability features: Whereas RStudio allows in-line interpolation in Markdown paragraphs (Literate programming), Jupyter has failed to provide such a feature after years of discussions (ipython #2592). The developers have explained the complexity of this feature under the current framework but IMHO a non-perfect solution is better than no solution. Other features that I have found useful but missing include but not limited to the ability to clear cell outputs (e.g. when output of a cell is really long and non-informative), the ability to execute long scripts without doubling braces in cell magics (e.g. magic %%script), and preview of variables even content of files.

SoS Notebook

When I started to implement SoS Notebook as a Jupyter kernel for a Python3-based workflow engine called SoS, it became obvious to me that I needed to expand the Jupyter frontend to provide a more comprehensive user interface for interactive multi-language data analysis. Although SoS Notebook is based on a workflow engine, you can use SoS Notebook as a Python 3 kernel with multi-language support because SoS is implemented as an extension to Python 3.6. The SoS workflow engine greatly expands the usability of SoS Notebook but it is a complete topic by itself and deserves a separate post.

The rest of this post will explain key features of SoS Notebook in details. Because wading through a long blog post can be boring, you are strongly advised to click the button at the top right corner of the SoS Homepage to create a new SoS notebook so that you can try the examples by yourself. It would be even better if you can watch the following video for an overview of SoS Notebook before you continue:

Multi-language notebook

The first thing you will notice from a SoS notebook is the language-selection dropdown boxes at the top right corner of each cell. This dropdown box allows you to change the kernel of a notebook cell to any of the installed Jupyter kernels (called subkernels in SoS Notebook). This allows you to, for example, execute a shell script using the Bash kernel in a cell, import data in Python (SoS), and analyze data in R using an ir kernel. In addition to the per-cell language-selection dropdown, you can also use the global language-selection dropdown to change the global default kernel for new cells.

Because you can use all Jupyter kernels in a SoS notebook and can set a non-SoS default kernel, you can use a SoS kernel for all your notebooks even if you do not use Python in your notebook. That is to say, even if you only use a single kernel in your notebook, using SoS as a wrapper to your kernel would allow you to enjoy all the frontend features that SoS Notebook provides.

SoS interpolates scripts before sending them to subkernels. However, unlike the iPython %%script magic that always expand

expressions in braces (e.g. {variable}), SoS by default does not interpolate cell content so that you can use

subkernels freely without worrying about the inclusion of braces in the scripts.

If there is a need to pass variables from SoS to the subkernels, you can use the

%expand

magic to expand expressions in braces with variables defined in the SoS kernel, essentially treating cell contents as f-strings of Python 3.6 (this is why SoS Notebook depends on Python 3.6). This allows you, for example, to pass a filename to subkernels so that you do not have to repeat it for each subkernel.

Furthermore, if your script in the subkernel

contains many braces, you can specify an alternative sigil so that you do not have to double the braces for string

interpolation. For example, in a cell with Bash subkernel, you can pass filename to the subkernel with sigil %( )

as follows if it is unsafe to expand the script with either { } or ${ }:

%expand %( )

for i in {1..4}

do

echo ${i} >> %(filename)

done

Note that SoS magics always expand expressions in braces, as show in the last example:

Inter-language data exchange

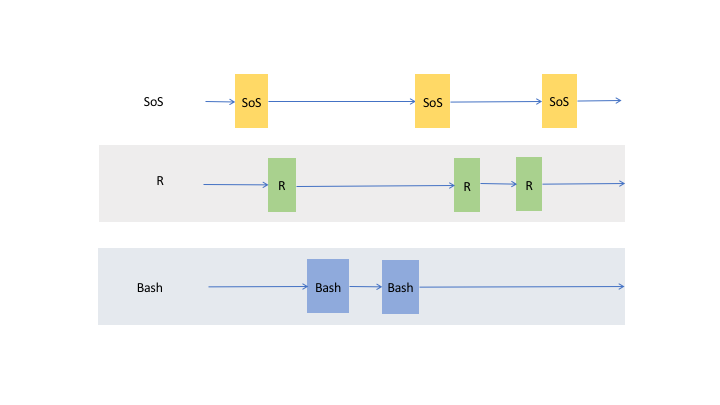

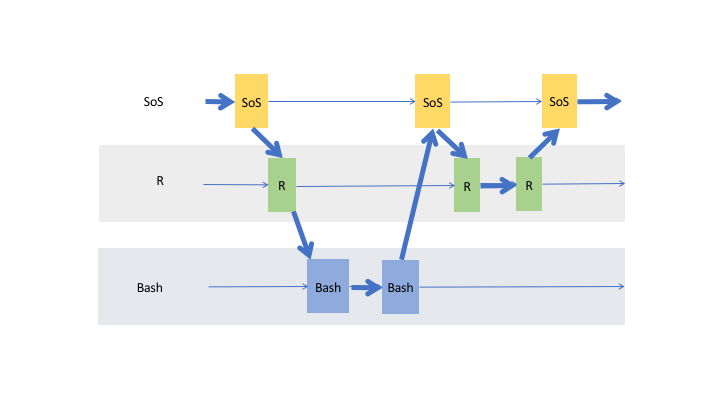

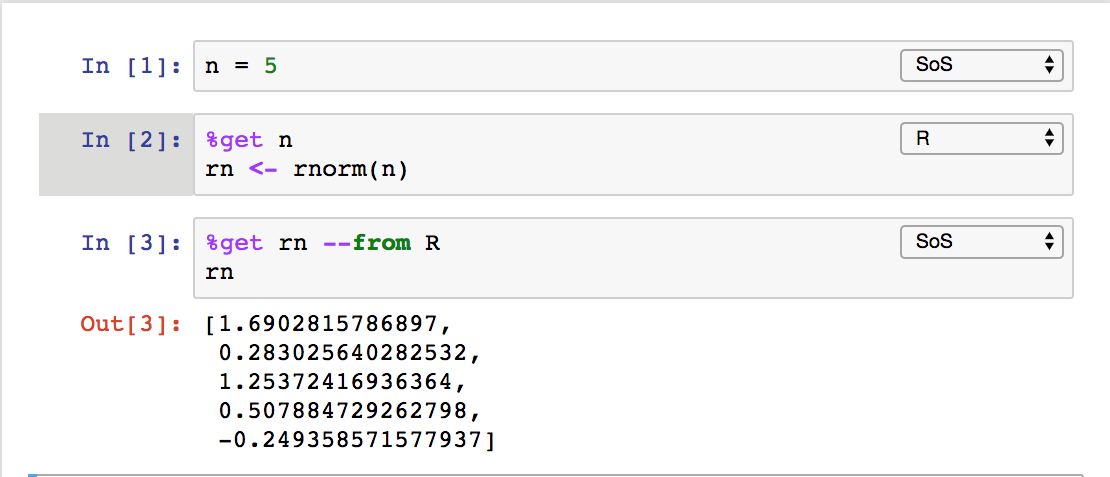

If you followed the animations in the first figure, you might have noticed another way to pass variables

from one kernel to another, namely the use of the %get magic. This magic allows you to

transfer variables from one to another kernel, so whereas it is correct to think of a SoS notebook with multiple

subkernels as multiple trains (cells belonging to each subkernel) running on their own tracks,

the data actually flow through cells of the same kernel and cross cells to other live kernels as shown in the following figure

This powerful data exchange model allows you to, for example, load and clean your data in Python, analyze them in R, SAS,

or MATLAB, and plot the results in other kernels such as JavaScript. The data exchange can be done explicitly with magic %get

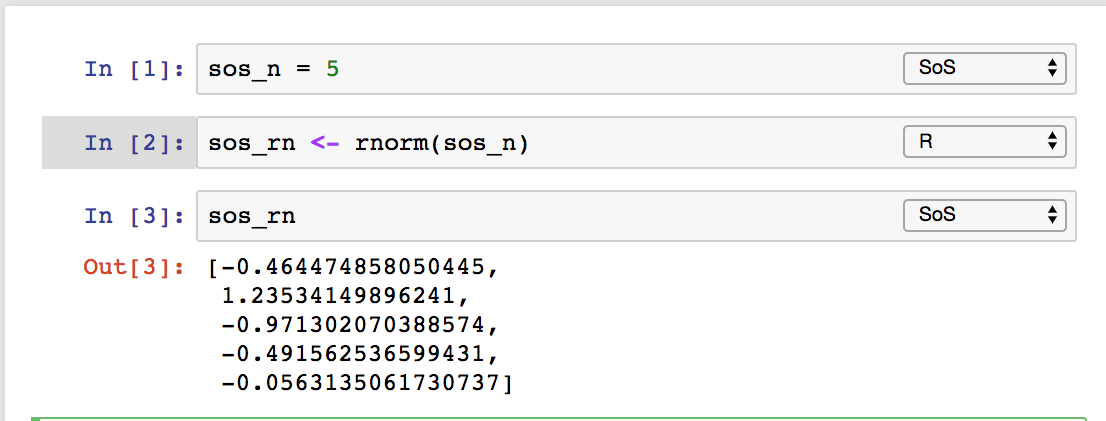

implicitly for variables with names starting with sos

or as side effect of kernel switch

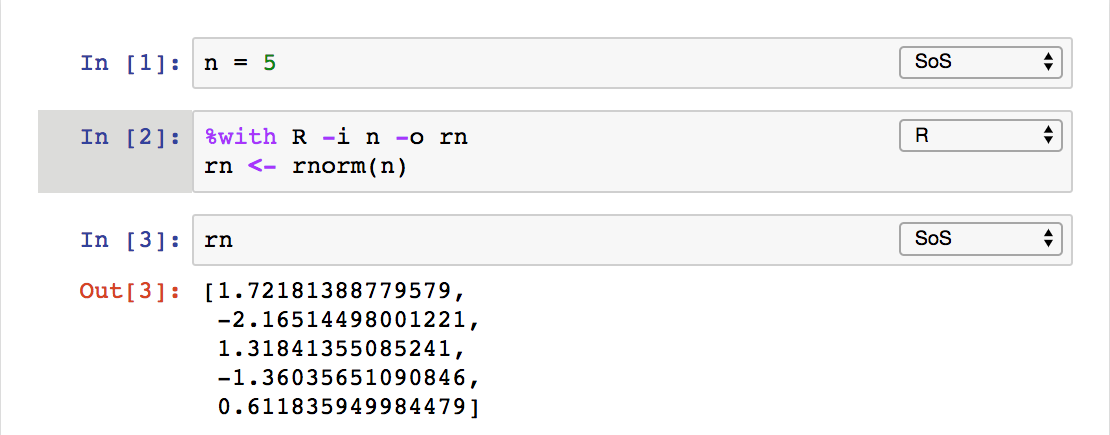

The last method that uses a %with magic is pretty interesting because it allows you to execute a cell in another kernel with input and

output variables, similar to calling a function.

Exchanging data of different types between live kernels in different languages is a very challenging task and requires coordination between sending and receiving kernels, either directly or by way of SoS. SoS currently supports data exchange of most native data types among SoS and nine supported languages and you are encouraged to check out the SoS manual on Supported Languages for details. However, just to answer a few questions you might already have,

SoS does not copy or transfer variables from one kernel to another. It creates independent homonymous variables in the destination kernel so that changing variables in another kernel does not affect the variables in the sending kernel.

SoS creates variables of similar types that are native to the destination language. For example, although

3andc(3, 5)are both numeric arrays inR, they are converted to Python as integer3and numpyarray([3, 5])respectively. Similarly, a PythonDataFrameis converted todata.frameinR,datasetin SAS,tableinMATLAB,dataframein Octave, and nested dictionaries in JavaScript.Data exchange might lose information if destination language does not support features of the source kernel. For example, most variables passed to

Bashwill be converted to strings and dataframes passed to Octave will lose row labels because Octavedataframedoes not support row label.Data exchange between subkernels is usually done by way of SoS (e.g.

kernel A->SoS->Kernel B) but the protocol allows direct data exchange between subkernels.

Side panel, line-by-line execution of cells

SoS Notebook provides a side panel that can be used to execute a variety of nonpermanent actions, namely actions that

are temporary in nature and with results kept outside of the main notebook. Such actions include executing scratch commands,

showing results of line-by-line execution, previewing variables and files

(magic %preview), and showing the table of contents

of the notebook (magic %toc).

The most important feature is the keyboard shortcut Ctrl-Shift-Enter for executing

selected code (or current line if no code is selected) in the side panel. As you can see from the following figure, the

side-panel automatically switch languages so you can step through your cells in any language.

Preview of variables and files

Instant feedback is crucial for smooth interactive data analysis so SoS Notebook went a long way in providing

a really powerful magic called %preview.

Basically, the %preview magic can

- Preview variables and expressions (quotation required if expressions contain spaces) in any kernel.

- Preview files in many different formats, including bioinformatic-specific formats such as fastq, vcf, and bam. Depending on the nature of the data, SoS Notebook shows images in different formats, lists contents of compressed files, and summarizes key information such as the length of reads for fastq files and the reference genome used for VCF files.

- Preview Python DataFrames in scrollable, sortable, and searchable tabular format, or in interactive scatterplot with a tooltip for each data point. These features make it easy to present and search large tables, show sample distribution and identify outliers of the data.

- Automatically determines whether the code is a single variable or an assignment statement and previews the resulting

variable. This works for different syntaxes in different languages (e.g.,

a <- 3in R) and is arguably easier to use than looking for a variable in a dedicated window that lists all variables in some IDEs.

The %preview magic also provides options to preview results in the side panel or main document,

preview files on local and remote hosts, save displayed results in the main notebook or side panel, and control

the style of preview results. Please refer to

the documentation of %preview magic for details.

Summary

SoS Notebook was started as a Jupyter kernel for the SoS workflow engine but evolved to a multi-language notebook to provide users with a comprehensive environment for interactive data analysis using multiple languages. This post lists several of its key features and there are more interesting magics such as

- A

%rendermagic to render output from any kernel as markdown, HTML, svg etc, which essentially allows inline string interpolation from any subkernel. - A

%clearmagic to suppress output of cells to be executed, or clear output of selected or all cells after they are executed. - A

%tocmagic to display dynamically updated table of contents in the side panel. - A

%sessioninfomagic to collect and display session information from all running kernels.

More details of these magics and SoS Notebook in general can be found at the SoS website from which you can find documentation on SoS Notebook, SoS Magics, Supported Languages, and videos from the SoS Video Library.

SoS Notebook is fairly stable for a new project but we would not want to make a 1.0 release without hearing from you. Please test SoS Notebook and send your feedback and/or bug reports to our github issue tracker. If you are interested in adding support for your favorite scripting language (remember that SoS supports all Jupyter kernels but can only exchange variables among supported languages), please check out our tutorial on adding a new language and discuss with us on github. If you find SoS Notebook useful, please support the project by starring the SoS and SoS Notebook github projects, or spreading the word with twitter.